There are people who will tell you that Ealing films – and particularly the comedies – are cosy, comforting, bland. These people should refresh their memories. They have forgotten how the hero of Kind Hearts and Coronets manoeuvres an elderly aristocrat into a mantrap and finishes him off with a shotgun; how the secessionists of Passport to Pimlico are reduced to catching food parcels hurled over a barbed wire fence; how, in Went the Day Well? Thora Hird commands the screen as a Nazi-killing Land Girl – a Home Counties Inglorious Basterd.

Maybe the Ealing world seems secure and stable because it’s so thickly populated by recognisable British types (bluestocking dons, vicars, post mistresses, bank clerks) played by a repertory company of beloved character actors. (Alec Guinness provided a whole rep company one man.) The studio, however, was a place of subtle radicalism. Under the owlish eye of Michael Balcon, the Birmingham-born son of refugees from the Lithuanian pogroms, Ealing’s filmmakers helped to establish the post-war consensus that produced the NHS and the welfare state.

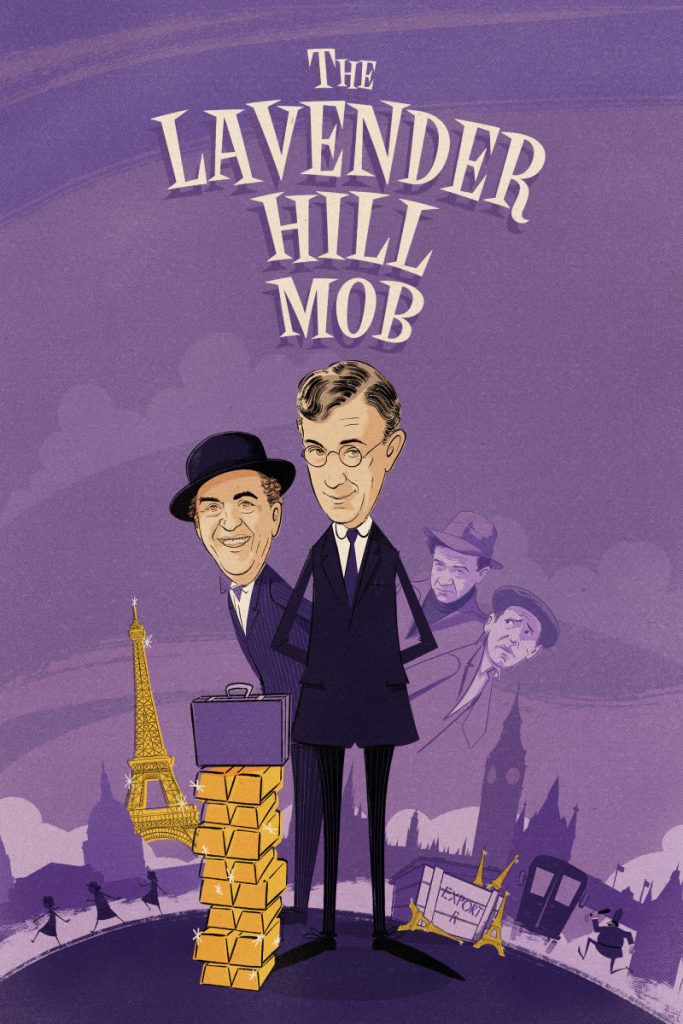

Ealing avoided propaganda. We cheer on the islanders of Whisky Galore as they hide bottles of contraband single malt inside babies’ cots, haystacks and rabbit warrens. We delight in the crimes of the Lavender Hill Mob, and don’t quite begrudge Alec Guinness’s escape to South America. We know that The Man in the White Suit has nothing reassuring to say about the British workplace. But this was the studio that went to war against the spivs and racketeers, acknowledged the frustrations of austerity, celebrated the unruly energy of the community.

When the studios were sold in 1955, a memorial plaque was bolted to the wall. “Here during a quarter of a century were made many films projecting Britain and the British character.” They shaped it, too.