Don’t look now. Actually do look. You can’t help it. It’s the warning that cinema audiences always disobey. And the compulsion comes naturally to British filmgoers, whose dreams have been haunted by Frankenstein’s monster, Martian war machines, and the horrors lurking on quiet country lanes or on the lonelier stretches of the London Underground.

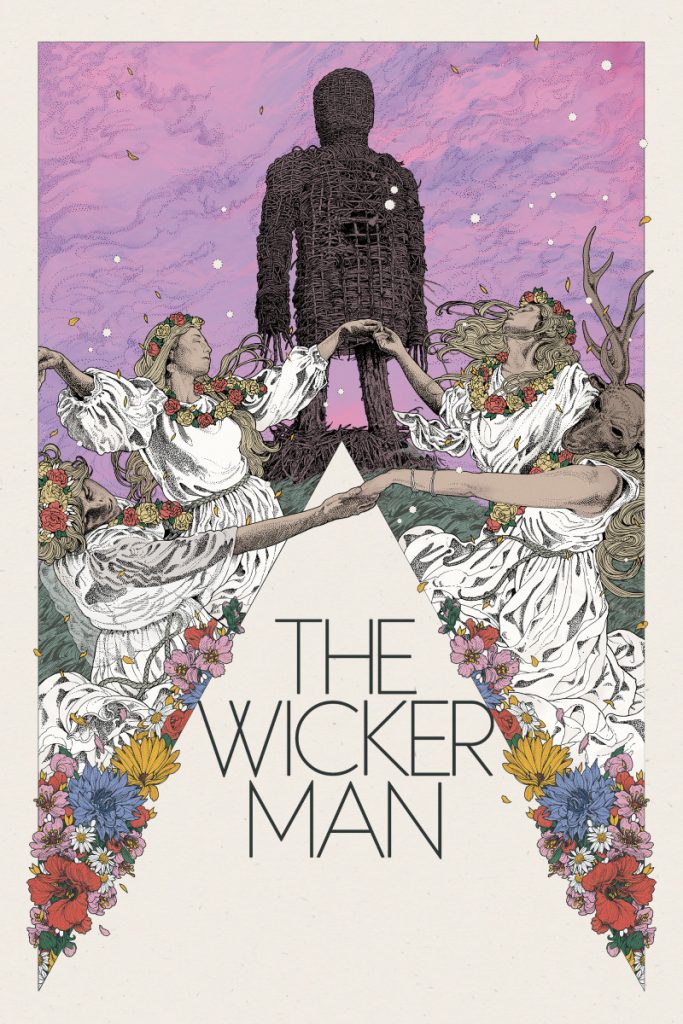

Some of the most memorable British movies seem to have come straight from the subconscious. Quatermass and the Pit brings ancestral monsters shrieking from the London clay. The holiday cyclists of And Soon the Darkness are followed by a pursuer who hunts them from the horizon, but keeps his distance. The policeman hero of The Wicker Man is alarmed by horribly legible Pagan imagery – maypoles, confectionary hares, teenage girls with flowers in their hair – before being consigned to the flames. Ealing’s Dead of Night is the horror portmanteau from which nobody can escape: once it has told its most blood-curdling story – the one about a sentient ventriloquist’s doll called Hugo – it simply loops back to the beginning. (It was influential, too: the astrophysicist Fred Hoyle saw it and proposed a new model of the universe.)

Nicolas Roeg, though, might be the director who best understood the fractured logic of nightmares. The Man Who Fell to Earth traps David Bowie’s lost alien on an Earth that seems as overpoweringly strange and hostile to us as it does to him. (No wonder he takes to drink.) Don’t Look Now is even more disorienting, cutting between images of dark water, spilt ink, surging rain. Nothing but the colour red links the accidental death of a little girl with a murderous being in Venice. But this is all that’s needed. When we’re asleep, we don’t question the logic of our terrors. Sometimes, in the cinema, we are also too scared to ask.