Are you angry about the state of Britain? Do you want change? Do you want equality? The dead share your desires. Cinema provides a record. It’s legible in The Holly and the Ivy, which takes us into a vicarage in post-war Norfolk, where the grown up children are struggling to navigate towards the future. It’s there in Last Holiday, in which Alec Guinness is a clerk who, believing himself to be terminally ill, escapes a life of bad faith. It’s there in Halfway House, a supernatural drama set in a Welsh country inn, where the guests go through experiences that force them to leave the past behind. A séance scene provides a moving moment in which a mother finally accepts the fact of her son’s death. (“Do you think he’d come clowning back tapping tables?” rages her husband. “Let him lie in peace.”)

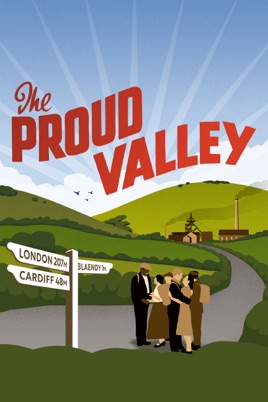

Two radical pictures chart the desire for a new world from the end of the 1930s to the first years of the peace. The Proud Valley is an Ealing studios drama about Welsh miners and racism. (Its message: “we’re all black down the pit.”) Paul Robeson plays an American sailor who finds work cutting coal in the Rhondda Valley, a place in the Eisteddfod choir, and a voice on the committee that negotiates with the bosses. It should have ended with the miners taking control of the pit and running it as a syndicalist co-operative, but wartime conditions required a more conciliatory conclusion. A decade later, An Inspector Calls restated those demands. In Guy Hamilton’s version of the JB Priestley play, Alastair Sim is the mysterious detective who arrives in a wealthy British household bearing the photograph of a young woman who has died in tragic and preventable circumstances. “We are responsible for each other,” says Inspector Goole, with clear, cold moral authority. “And I tell you that the time will soon come when, if men will not learn that lesson, then they will be taught in fire and blood and anguish.”