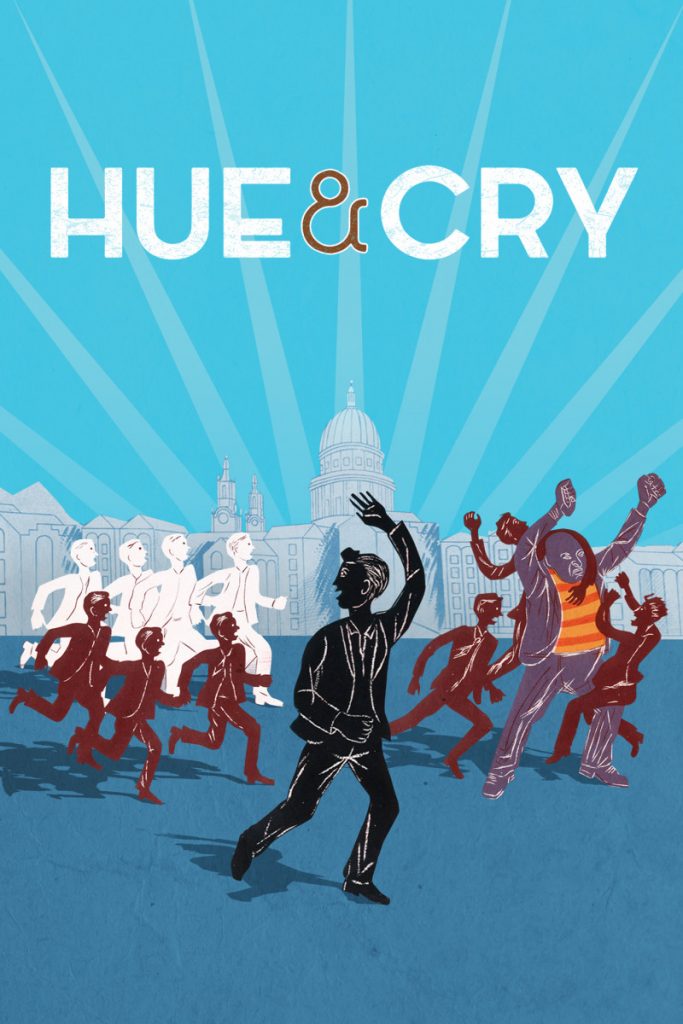

If you want to know how a society is doing, look to its children. Kids were rarely the centre of attention in wartime films. Post-war British cinema is noisy with them. They’re often sources of comedy and uproar – think of the hockey-stick-wielding terrors of The Belles of Trinians, or Harry Fowler and his gang, running the villains over a bombsite at the end of Ealing’s Hue and Cry. But more usually, they’re canaries in the coalmine of the nation’s morality.

Blame A Diary for Timothy, perhaps – the Crown Film Unit documentary that asked its audience to think about the country into which the babies of 1945 were being born. After that, fiction films seemed suddenly compelled to portray the desires and fragilities of children with new detail and intensity. The child actors of post-war Britain had an important role to play – to help British families recover from the emotional glaciation of those years of conflict.

Anthony Asquith’s The Winslow Boy, based on the play by Terence Rattigan, looks back to a famous Edwardian case – that of a public schoolboy accused of stealing a five-shilling postal order. (The responses of the adults tell us what kind of country we’re living in, and we note that one of his staunchest defenders is his suffragette sister.) Carol Reed’s The Fallen Idol features a remarkable performance by Bobby Henery – as a boy taking refuge from his cold and distant parents in friendship with their butler. Alexander MacKendrick’s Mandy puts us inside the head of a little deaf girl in the adoption system, and gives us all a lesson in compassion.

Eventually, the children of that generation started making films for themselves. Melody suggests they were more interested in finding love than solving crime. But in his London childhood, its director, Alan Parker, might easily have one of Harry Fowler’s gang of tearaways.